Schley, Jacob van der, ‘Plan de Jedo – Platte Grond van Jedo,’ in Prévost d’Exiles, Antoine François, Histoire Generale des Voyages (La Haye: De Hondt, 1747–1768, nouvelle éd. revue sur l’original Anglois), vol. 14: ‘Voyage d’Engelbert Kaempfer au Japon,’ pp. 296–297, copper-etched, 25 x 24.5 cm; ETH Library Zurich, Rar 5738, DOI: https://www.e-rara.ch/zut/content/pageview/3663515

‘Maps […] are always more than mere factual statements. They are translations of reality into forms we can master; they are fictions and acts of imagination communicating more than scientific data. So they reflect changes in our pictures of reality.’

Roberts, John M., The Triumph of the West (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1985), p. 194.

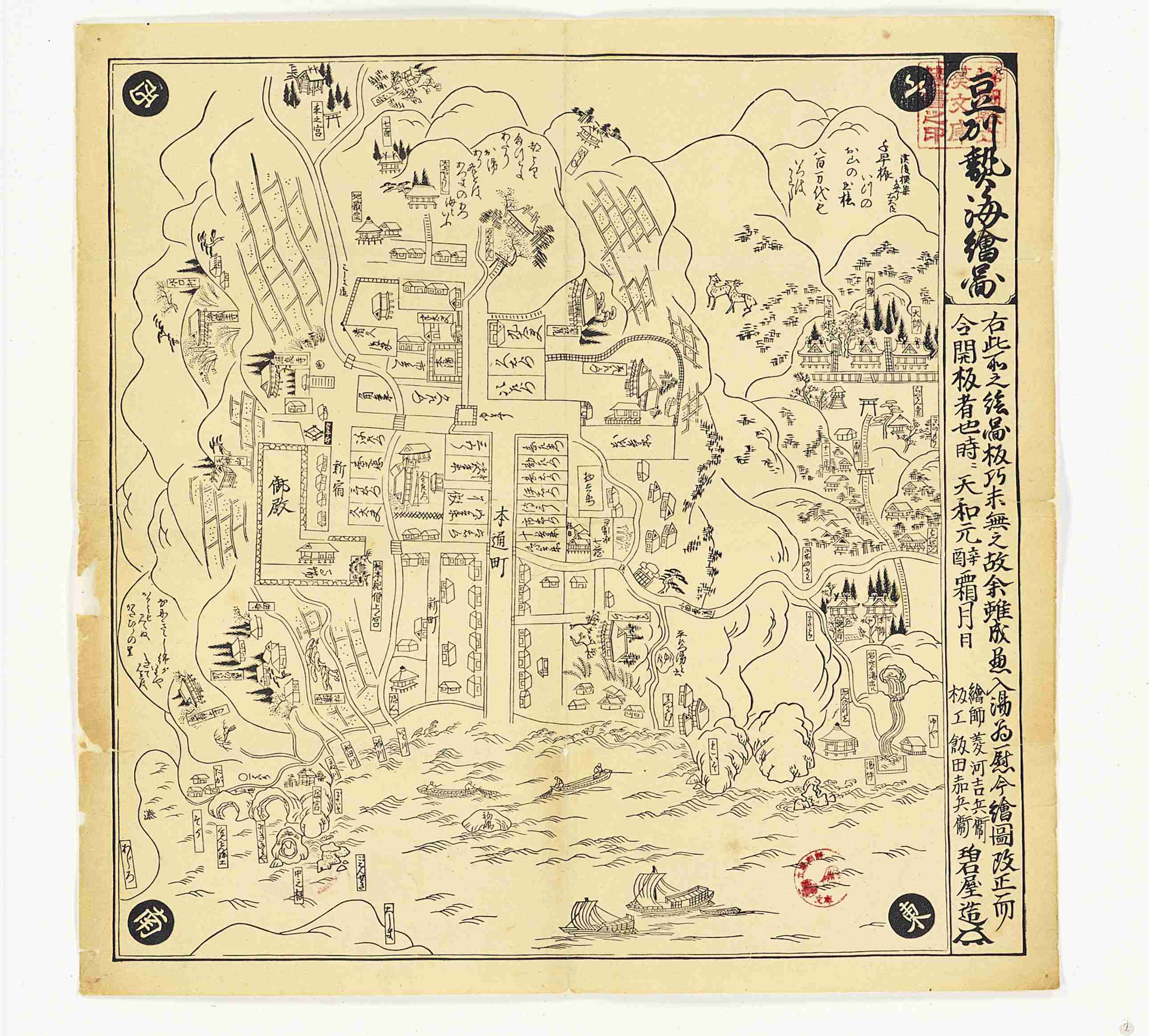

Can you agree with John M. Roberts that maps are ‘fictions’ that ‘reflect changes in our pictures of reality’? Roberts’s idea refers to the first argument of this unit, namely that maps mirror shared belief systems and world views. A mid-eighteenth-century European map illustrates this argument. It shows the spiral plan of Edo (present-day Tokyo) in accordance with Japanese maps. But its Dutch illustrator Jacob van der Schley (1715–1779) has filled Edo castle grounds, forming the center of the map, with a French formal garden. Schley's map suggests that gardens are indispensable elements in the imagination of aristocratic houses in early modern Europe. Maps are sometimes intentional manipulations, by referring to particular place names (Japan Sea, East Sea) or omitting particular data (the distribution of radiation) respectively, which trigger a sense of crisis (geopolitical conflict, environmental change).

You might object that maps are more often than not quite precise representations of absolute space. In response to this objection, the second argument of this unit is that maps can offer a glimpse into ‘real’ historical conditions. Mid-nineteenth century Japanese maps of Edo, for instance, show that daimyo storehouses were found east of Sumida river in the commoner quarters, whereas merchant shops were located within the area of the western hills, reserved for daimyo residences. The maps suggest that socio-economic divisions were far less pronounced in the practice of everyday life than in the status ideal propagated by the political elite.