The ‘four portals’ (yotsu no kuchi 四つの口) in Japan in the Edo period; link to the full screen: https://j-images.ch/map/4MouthsofEdo.html

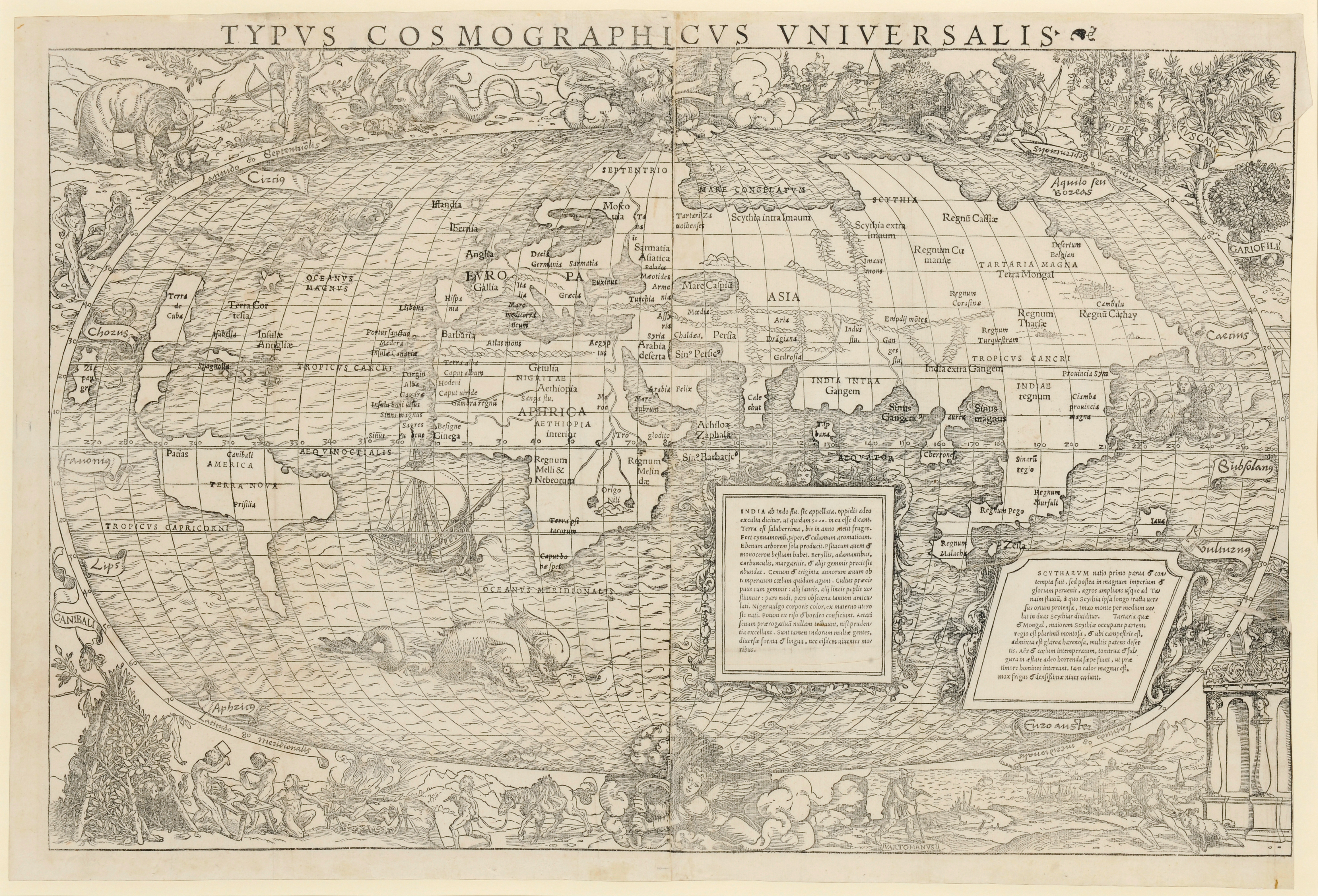

The battles between the 1560s and 1600 were repercussions of a century of warfare and stand in contrast to the subsequent pax tokugawa. The divide between the so-called Azuchi-Momoyama (1573–1603) and Edo periods (1603–1868) is not only reflected in war versus peace, but is also found in other spheres of life: foreign explorations versus permeable isolation – Katō Eiichi contrasts the ‘age of the great voyages’ (daikōkai jidai) with Japan’s ‘national seclusion’ (sakoku) – horizontal alliances versus a hierarchical political order, occupational fluidity and social mobility versus disciplinary control, women’s property rights versus patriarchic family structures, and a culture of pomp versus an ideal of austerity, propagated by the elite.

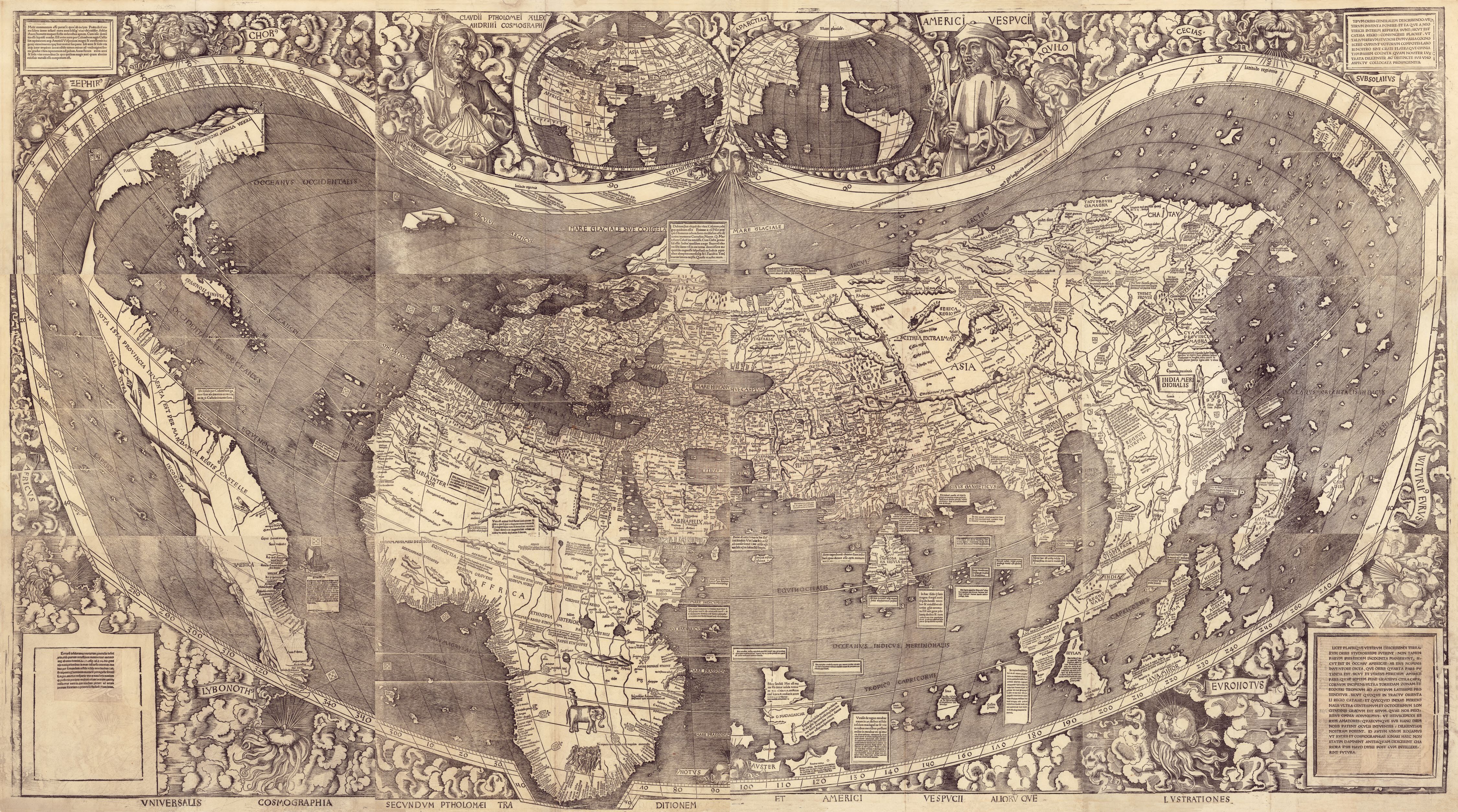

Yet, political, economic and social transformations were legato rather than staccato. First, the shogunal decrees that proclaimed ‘maritime prohibition’ (kaikin) in the 1630s brought an end to Japan’s participation in the Manila-Acapulco trade. But exchange with the outside world continued throughout the Edo period: Nagasaki received Chinese and Dutch ships; Tsushima Domain oversaw diplomatic and trade relations with Joseon Korea; Satsuma Domain maintained exchange with the Kingdom of Ryūkyū (present-day Okinawa Prefecture) to the south; finally, Matsumae Domain, located at the southern tip of Ezo (present-day Hokkaido), conducted trade with the Ainu to the north.

Second, though the last medieval battles gave rise to the monopolization of law under the Tokugawa shoguns, daimyo preserved their decision-making authority in the provinces. Third, the establishment of castle towns and the sword hunts in the 1570s and 1580s led to the dissolution of warriors from agricultural processes and lay the basis for a status-oriented society, divided into samurai, peasants, artisans and merchants (shi nō kō shō). Nevertheless, merchant and peasant households, some of which had risen to political visibility in the late sixteenth century, retained an important position in the economic and cultural life of the Edo period. In summary, the late-sixteenth-century processes were not only antagonistic to but also a pre-condition to formations of ‘early modernity’: political unification, which promoted domestic economic and social networks and supported the notion of ‘Japan’ as distinct from the outside world, as well as regional and social cleavages, which shaped the identity of the elite in domains and the every-day life of status groups.