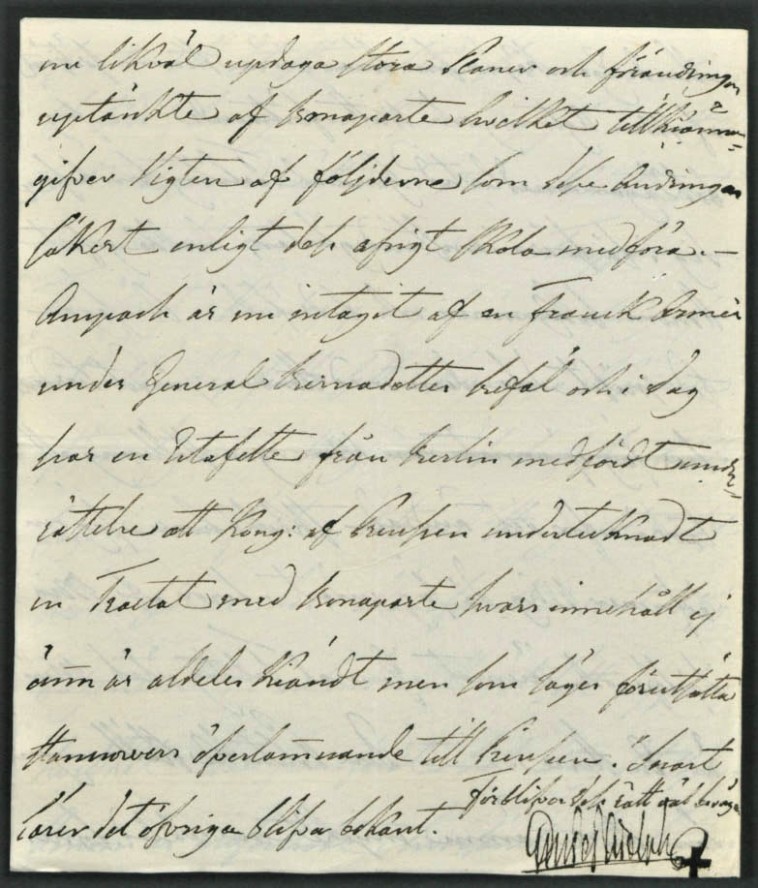

Petter Claesson 1776

National Archives of Finland, http://digi.narc.fi/digi/view.ka?kuid=42131218.

Literature:

- Koskinen, Ulla, Kirjeenkirjoittamisen taito. In Keskiajan avain. Ed. Marko Lamberg, Anu Lahtinen & Susanna Niiranen. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura – Helsinki 2009, pp. 404-405.

- Koskinen, Ulla, Hyvien miesten valtakunta. Arvid Henrikinpoika Tawast ja aatelin toimintakulttuuri 1500-luvun lopun Suomessa. Bibliotheca Historica 132, Tiede. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura – Helsinki 2011 .

- Kuusanmäki, Jussi, Yksityisluontoiset asiakirjat. In Suomen historian asiakirjalähteet. Kansallisarkisto & WSOY – Porvoo 1994. pp. 275–291.

- Nikula, Oscar, Petter Claesson, turkulaisten 1700-luvun merenkulkijoiden eräs edustaja. In Turun historiallinen arkisto 33. Turun historiallinen yhdistys – Turku 1979. pp. 99–124.

- Runebergistä riimuihin. Website: https://www.jyu.fi/gammalsvenska/ (accessed 19 December 2017)

Die Transkription lautet:

Herr Capitaines härigenom hafdaÜbersetzung:

möda skall jag på alt upptän-

keligt sätt söka aftjena.

The troubles Mr Captain has had so far

I shall by all thinkable

means try to compensate.

More loosely translated:

I shall try to compensate

the troubles the captain has had so far

by all conceivable means.

Letters sent from and in many cases to the authorities were often composed by more or less skilled scribes. Although in the sixteenth century, for example, nobles were able to write letters themselves, they often used scribes, at least for their official correspondence. Peasant literacy was generally so poor that they always used scribes to compose letters and documents at least until the nineteenth century. Scribes were used for other reasons than poor or non-existent literacy. Documents including letters were to be composed according to a specific formula and style, depending on the recipient. At least until the sixteenth century, correspondence conventions were based on medieval letter-writing theory (ars dictandi) which was seen as part of rhetoric. Therefore, composing letters required special skills of the writer. When the author had presented what he or she wanted to say to the letter’s recipient, it often remained the task of the scribe to express the message in a style and form appropriate to the recipient’s status and position. The date is usually at the beginning of the letter, in the upper right-hand corner, or at the end with the signature. The letter itself begins with a greeting (salutatio), which reflects the position or status of the recipient and the sender’s relationship to the recipient. In general, the letter opens with a prologue (capitatio benevolentiae) in which salutations are given. Sometimes these phrases may be longer than the subject of the letter itself. The prologue is followed by the actual matter at hand (narratio) and possibly a request (petitio). The letter concludes with more courtesies and greetings to any other persons (conclusio) if, for example, the author of the letter is personally acquainted with the recipient’s family. The letter closes with a final greeting and then the sender’s signature. If the sender has written the letter herself or himself, or at least signed it, the signature is confirmed by printing “manu propria” (in my own hand) after the name and drawing a sort of criss-cross pattern below the signature.