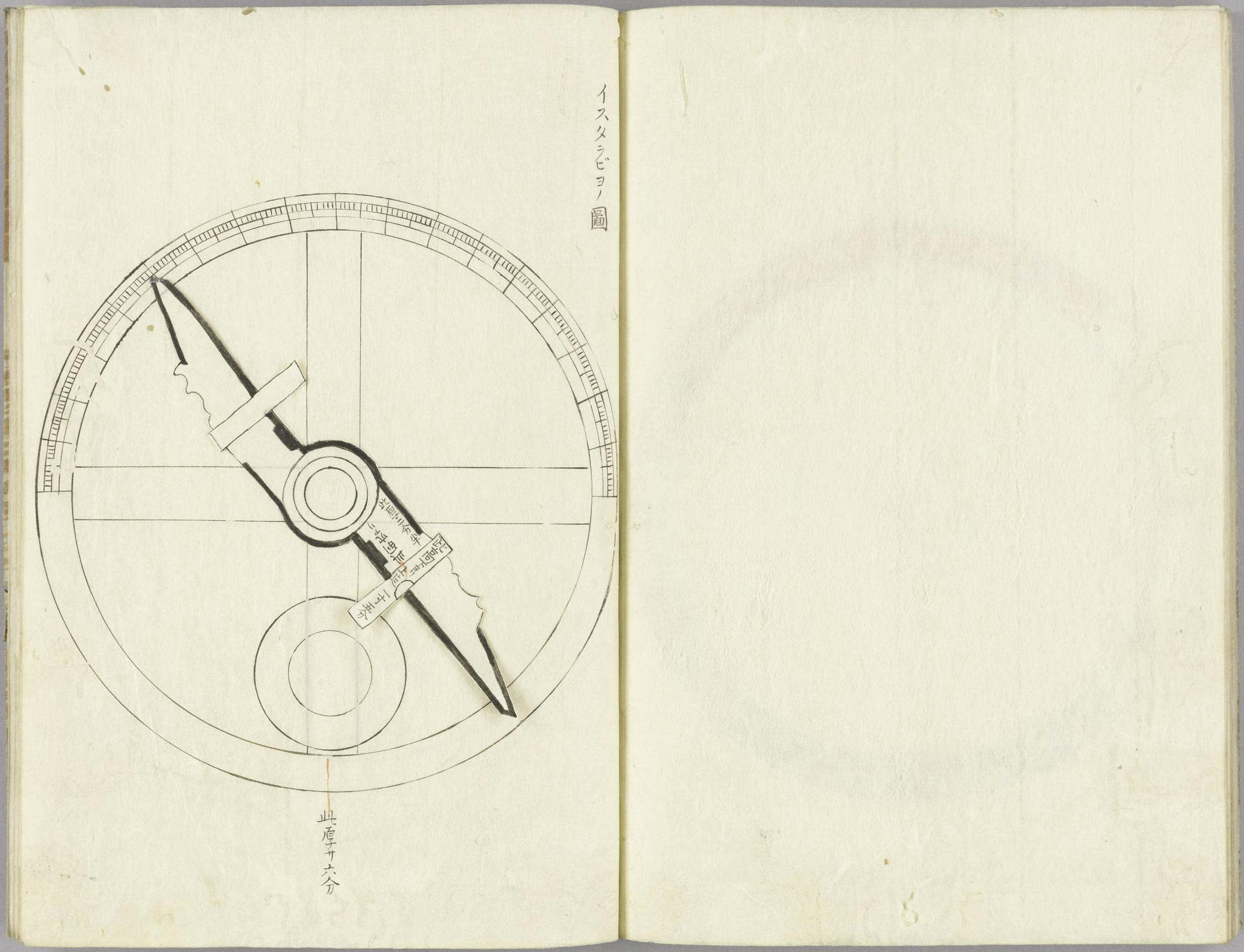

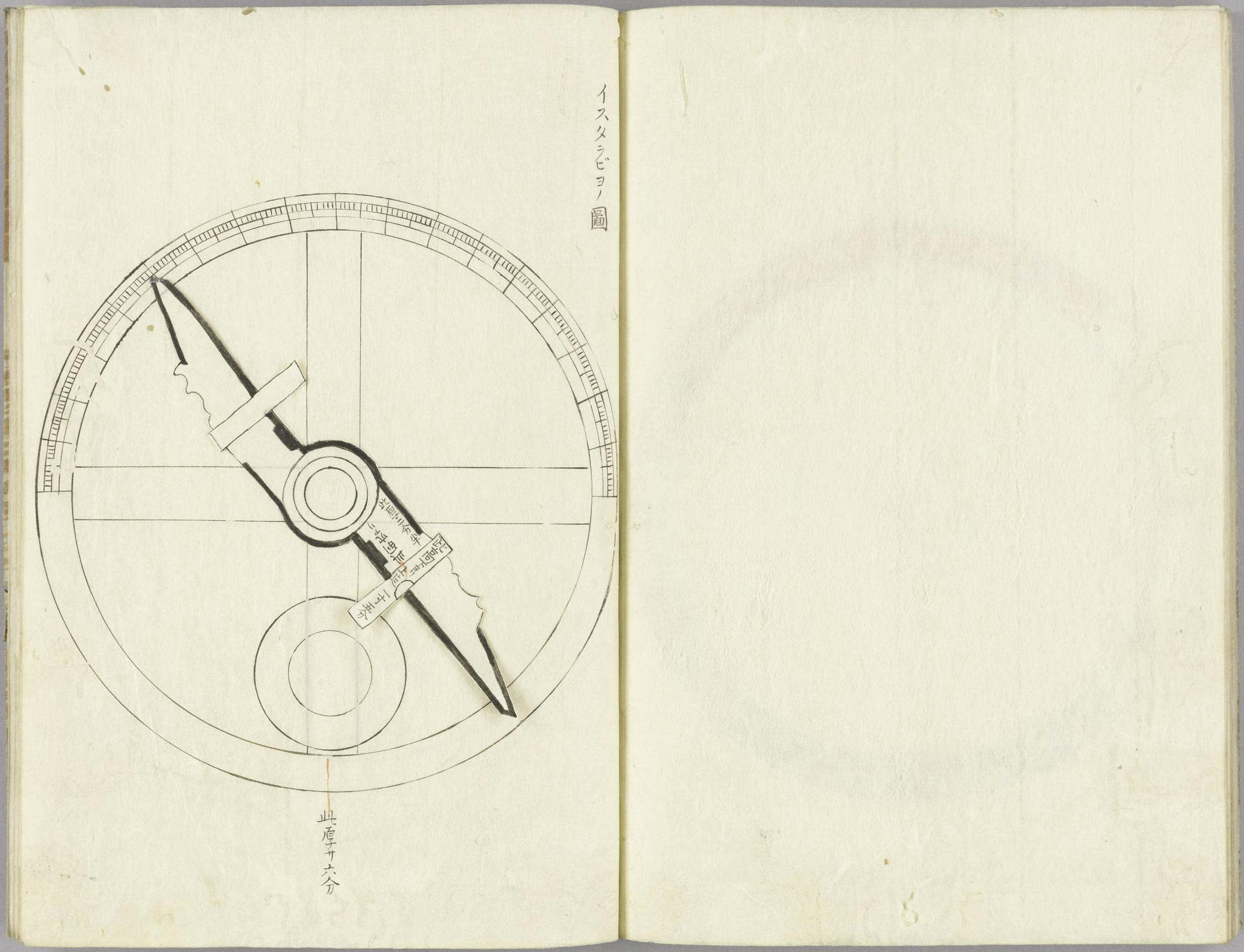

‘Astolabe,’ in Hosoi Kotaku 細井広沢, Hiden chiiki zuho daizensho 秘伝地域図法大全書, [s.n.: s.d.], vol. 3, National Diet Library Tokyo, URL: http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/3508801/36 ;

cf. Unno Kazutaka, “Cartography in Japan,” in Harvey, B. and D. Woodward, eds., History of Cartography (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), p. 393; Frumer, Yulia, Making Time: Astronomical Time Measurement in Tokugawa Japan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), p. 98.

The Jesuit Alessandro Valignano (1539–1606) writes:

From olden times the Japanese have had geographical maps of all these islands, but as they had no knowledge of cosmography and knew nothing about degrees and the elevation of the pole, they had no reliable and good drawings. They also did not know accurately the position and latitude of the islands.

cit. in Schütte, Jos. Fr., ‘Ignacio Moreira of Lisbon, Cartographer in Japan 1590–1592,’ Imago Mundi 16 (1962), pp. 116–128, here: p. 123.

In the Hiden chiiki zuho daizensho of 1717, Hosoi Kotaku also refers to the importance of astonomical observation for accurate mapping. He introduced the neologism ‘surveying’ (測量 sokuryō), by shortening the Chinese ‘observe the sky and estimate the earth’ (sokuten ryōchi 測天量地). He argued that the greater part of measurement methods had been introduced from China more than thousand years ago, but that to determine the position of a place the integration of ‘Dutch’ astronomical measurement was also necessary.

Just several decades earlier, Yasui Santetsu, the younger (alias Shibukawa Shunkai, 1639–1715), had made a map, in which he estimated the latitudes and longitudes of western Japan, and in 1678 he had localized Mafu in Edo to 35°38' (implying only 1'17" diference to Meiji-period surveys). Shibukawa is also known for having built the first terrestrial globe in Japan. In 1719, the eighth Tokugawa shogun Yoshimune (1684–1751), a promoter of calendrical and astronomical computation and the founder of the observatory in Edo's Kanda quarter, ordered Takebe Katahiro (1664–1739) to make a revised map of Japan. Katahiro based his map, completed in 1723 and revised until 1728, on the fourth shogunal survey project of provinces, initiated in 1697. But he also used a lodestone to determine directions and unified the scale in the map.

In 1800, Inō Tadataka (1745–1818) began surveying the whole coast of Japan. His students completed his project in 1821. Tadataka relied on established survey methods of triangulation and distance measurements during day time. But he also based his survey on astronomical observation at night time, by using a sextant, a meridian device and a pendulum clock, the latter allowing him to time celestial phenomena. A section ‘Middle-of-Night Obervation’ (Yonaka sokuryō no zu 夜中測量之図)’ of a picture scroll, with the title ‘Pictures of Urashima Survey’ (Urashima sokuryō no zu 浦島測量之図), of 1806, held by Irifuneyama Memorial Museum (Kure City, Hiroshima Prefecture) shows Tadataka and his survey team at work. The survey allowed in particular to accurately map Ezo (present-day Hokkaido). The so-called ‘complete map of Japan's coast lines’ (Dai Nihon enkai yochi zenzu 大日本沿海輿地全図) or ‘Inō maps’ (Inō-zu 伊能図) (online via the Library of Congress) were used and copied until the Meiji period.